The Duke Who Loved Tunnels So Much He Was Immortalized As A Literary Badger

Webleck Abbey circa 1829, populated by the deer the 5th Duke liked more than people. (Image: John Preston Neale/WikiCommons Public Domain)

William John Cavendish-Scott-Bentinck, The 5th Duke of Portland, was never meant to be a duke. The job was supposed to go to his older brother, but he died too young, and when their father, the 4th Duke of Portland, followed suit in 1854, William John took up the title reluctantly. He didn’t like speaking in Parliament, and he refused most of the honors that went with his position. It took him years to accept his seat in the House of Lords. Really, he didn’t like talking very much at all.

In fact, there were only a few things the 5th Duke of Portland did like. He liked gardening and hunting. He liked horseracing and the opera. And he really, really liked digging enormous tunnels underneath and around his massive estate.

Though history is fuzzy on the exact numbers, we know that during the 18 years he was actively in charge of Welbeck Abbey, the 5th Duke of Portland oversaw the digging of at least a dozen miles of tunnels. He dug glass-topped tunnels tall enough for fruit trees, and flat-bottomed tunnels wide enough for horses. He dug rough-hewn tunnels for workmen running parallel to fancy tunnels for gentry. He excavated huge underground atria—a ballroom, an observatory, and a billiards hall. He dug so many tunnels, he is likely the inspiration for Mr. Badger in Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows, the gentle Lord of the Wild Wood who famously believed that “there’s no security, or peace or tranquility, except underground.”

In this illustration from The Wind in the Willows, by Paul Bransom, Mr. Badger leads Ratty around his beloved underground domain. (Image: Paul Bransom/WikiCommons Public Domain)

Before he was memorialized as the dignified Badger, the Duke was the target of a lot of taunts. “During my school days we heard many stories about the ‘Mad Duke of Portland,’” writes T.K.S., a Warsop resident, on a local history site. Some assumed he had many lovers sneaking through the tunnels. Others said the opposite—that he made secret trips to the rectory, to pray in peace. Still others whispered that the Duke had been disfigured by a terrible disease, and used the tunnels to go to and fro with minimal pointing, laughing, and contagion.

The truth was likely less dramatic. Tunneling just suited the Duke. He was a man who appreciated his privacy so he built enormous walls around his beloved gardens, and put doors on his bed so no one could tell if he was in it or not. Legend has it that every day he ate one roast chicken, half for lunch and half for dinner, posted to him at midday through a letter-box in his bedroom door. The first word of his entry in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography—after his title, of course—is “recluse.”

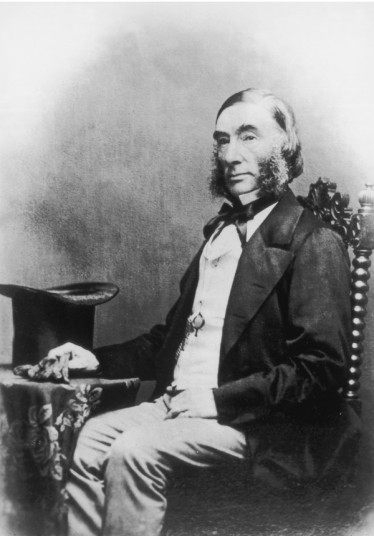

The 5th Duke of Cavendish, with his signature top hat. (Photo: Telegraph/WikiCommons Public Domain)

This love for solitude may not have moved mountains, but it did move a whole lot of dirt. This made it a fantastic job-creation program in a community that really needed it. Early 19th century Worksop was an impoverished place, and the Duke, T.K.S. writes, provided thousands of men with steady employment for nearly two decades of constant digging, dredging, and construction, aided by the latest in tunneling technology. Most of the tunnels were constructed through “cut and cover,” which involved digging a trench, building a wooden tube within, and covering everything up with dirt again. In 1878, a visiting journalist said the state of the abbey suggested “some great contractor who had an order for the building of a big village.”

Accounts of the Duke’s one-on-one relationships with these workers vary. Some maintain that he refused to be greeted by them, and even fired one for tipping his hat. Others say he regularly talked shop with the gardeners, gave his construction crew rowing lessons on the estate lake, and even used his tunnels to pop up among them as they worked. Though the Duke housed many of his employees on the property, the motive behind this gesture is similarly contested. Some praise his 19th century health plan, which provided doctor’s visits, food, and fuel delivery to sick employees and their families, as well as continued housing to workers’ widows. Others say the lodgings were little more than a slum, a way to ensure a constant supply of ill-treated Irish immigrants who would work for cheap.

He did build his employees a roller rink, and provided each of them with “an umbrella, a suit of clothes, a top hat, and a donkey” for transportation across the wide estate, a couple of unequivocal goods which earned him another one of his nicknames—”The Worker’s Friend.”

Inside the ballroom, later transformed into a “picture gallery.” (Photo: George Washington Wilson/WikiCommons Public Domain)

Inside the ballroom, later transformed into a “picture gallery.” (Photo: George Washington Wilson/WikiCommons Public Domain)

Said workers rewarded this friendship in spades. Though the exact lengths, widths, and depths of their work are muddied by myth (and by the fact that an army training college now occupies the estate, making it difficult for enthusiasts with rulers to access), their accomplishments are legion. They made an underground library, a glass-roofed observatory, and a billiards room. Most impressively, they dug a 10,000 square foot Great Hall out of solid clay, painted the ceiling to look like a sunset, and carved out beautiful bull’s-eye skylights to let in the sun. At the time, it was the largest unobstructed floor in England, because it didn’t need support beams. It was meant to double as a ballroom, and was accessible by hydraulic lift, but the Duke never invited anyone over—he preferred to use it as a solo roller-skating rink.

Then there was the warren of passages that didn’t even pretend to be for the public good, like the set of small tunnels that criss-crossed under the estate, into which the Duke would descend through a trap door, so even his servants didn’t know if he was home or not. One of the longest tunnels, wide enough for a horse-drawn carriage, went all the way from the estate to the nearest train station, allowing the Duke to make trips to London without anyone realizing he had gone.

As the Duke aged, he stopped even wanting to go that far. His world encompassed just five rooms of his estate—he had toilets installed in each of these rooms, and painted them pink. Six months before his death, he drove through his beloved tunnels one last time. He spent his remaining days in London, and was buried at Kensal Green cemetery with, the Oxford Dictionary says, “the utmost simplicity.”

The Webleck Estate today. (Photo: Tim Heaton/Geograph CC BY-SA 2.0)

A few years after his death, a strange lawsuit brought the Duke back into public life. In 1907, a man named George Hollamby Druce claimed that the 5th Duke of Portland had, with the help of his many tunnels, lived a double life—that he masqueraded as an upholsterer named Thomas Charles Druce, the grandfather of George. When the Duke had tired of this alter ego, he’d faked his own death, buried a weighted coffin, and returned to the Abbey. Thus, the logic followed, the Duke’s fortune rightfully belonged to George. His case made its way through the courts and ended with investigators digging up Thomas Charles Druce’s tomb—revealing, of course, the body of the real Thomas Charles Druce. Though this case came to nothing, George’s fake testimony, full of fake but juicy details about the reclusive Duke, reignited interest in him.

That was when newly won over fan, the writer Kenneth Grahame, penned a slightly disguised Duke into his masterwork, The Wind in the Willows. In the book, the magisterial Mr. Badger rules his kingdom, the Wild Wood, with an iron claw from his underground lair. While touring the impressed Mole around, he explains how the tunnel is actually the sunken ruins of a formerly aboveground city. “But what has become of them all?” asks Mole:

Who can tell?” said the Badger.“People come—they stay for a while, they flourish, they build—and they go… But we remain. There were badgers here, I’ve been told, long before that same city ever came to be. And now there are badgers here again. We are an enduring lot, and we may move out for a time, but we wait, and are patient, and back we come. And so it will ever be.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook